Finding What Fits: Your Native Plant Community

Step 2 in How to find the best native plants for your garden

Last week I wrote about ecoregions, naturally defined areas with similar habitats and ecosystems. This week I am going to explore natural vegetation classifications and native plant communities. Put your plant geek hat on - this gets a little nerdy!

I’ll offer a Choose Your Own Adventure element: if you are not in the mood or not ready to get into the finer details, you can take some quick shortcuts to begin finding great native plants for your general area - and this will be the perfect starting place as you plan out your home landscape. Or, if you really want to drill down into some of the nitty gritty, you can choose that option as well in order to gain a greater understanding of the naturally occurring plant communities in your immediate vicinity. To be clear, I am providing a number of different options below. Try one or try them all - whatever floats your boat. You do not need to follow every step in the order I’ve presented them.

Why should I care about native plant communities?

The more you understand about what grows naturally around you, the more closely attuned and aligned you will be in your gardening efforts.

First and foremost, by matching even some of the plants that occur in your area, you will be doing a great job of supporting your local wildlife.

Second, by mimicking the existing landscape patterns, you’ll have better luck with garden success. Instead of trial and error with random “native” plants, you will be able to identify the precise species that have evolved for your soil and climate conditions.

Finally, as you become familiar with your local flora, you will develop greater insight into how everything connects. You will be able to identify plants in the wild as you walk around; you will notice interdependencies and relationships between plants and wildlife; and this knowledge can add significantly to your enjoyment and appreciation for the natural world.

I will walk you through a step-by-step process to discover your particular plant community - read on!

Choose Your Own Adventure Option #1: Take me straight to some plants

Here are four ways to quickly generate lists of plants native to your area:

Use National Wildlife Foundation’s Native Plant Finder by ZIP code to generate a list of plants that occur roughly in your area.

Visit the National Audubon Society’s Plants for Birds website and put in your ZIP code and email address to get a personalized list of native plants that help birds (they will also benefit other forms of wildlife, of course!).

Go to the Wild Ones What’s My Ecoregion to find a list of excellent keystone species. This is a great way to quickly identify plants that have rich wildlife value.

Discover Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center’s Recommended Species list by state. Because this will give you a statewide list, it is not tailored to your specific area, but it can provide a good cross-reference list because it only includes plants that are commercially available.

For those of you who are just starting out, or who don’t want to get too deep into botany and ecology, the options above are solid starting points. You don’t have to make yourself crazy trying to figure all of the nuances out! The important thing is to start. Any native plants you can add to your landscape will absolutely be of great help and you can feel confident that you are bringing benefits just by choosing species from lists you get here.

Choose Your Own Adventure Option #2: Figuring out what grows near you

I am not going to lie: the rest of this post is going to take us down some rabbit holes, and you might feel even more confused or twisted up after doing your own investigations. I have certainly spent a fair bit of time trying to figure out what all of the datasets are, what they mean, and how to go about finding them. I still don’t have an easy, streamlined process by any means, so at this point we are pretty much in this together, feeling our way along.

But what I WILL say is that, even if at first it doesn’t make sense, or you are left wondering how to integrate this information, you are still building your knowledge and providing yourself with more context as you continue your ecological gardening journey. And remember that it IS a journey. There is always more to learn. On that note, if you have additional knowledge, insight, or direction to impart, please share in the comments below!

So begins a process of triangulation to narrow in on the plants that naturally occur in your area. Your searches and results will vary based on your state and your level of interest in specificity.

Find County Plant Lists

You may want to have some ready references that you can check when you are out plant shopping, or when you are trying to design a garden bed. To find a list of all plants native to your county (which will still be quite broad, floristically speaking - many different kinds of habitats occur within a county - e.g., wetlands, hillsides, valleys, slopes, etc) - This is a good starting place and a way to find excellent cross-reference lists:

USDA PLANTS Database - search by state and county to generate a full list of plants native to your county. **Be SURE to then narrow the list by checking the box next to Native L48 (if you are in a state in the contiguous US). Then you can download the list as a spreadsheet in .csv format which can be imported into Google Sheets or Excel.

For a list that is probably slightly more botanically correct, if you live in Virginia you can go to the Digital Atlas of the Virginia Flora. Choose Browse by County, click your county name, then choose Vascular plants. A very long list will appear. Then you can download the County list of plants. **BE SURE when you open your spreadsheet that you filter out the “I” for Invasive plants so that you are left only with the “N” for Native plants in the Native Status Column!

For those of you in other states, find your native plant society at the North American Native Plant Society website and explore the plant list/database offerings there. Most states will probably have county lists like Virginia’s.

Download a full list of plants native to your ecoregion

If you got excited by last week’s post on ecoregions, you can research all of the plants native to your ecoregion at bplant.org. This is a rich resource for both generating a list and also for researching specific plants. It is a mostly volunteer effort and continues to be developed. So cool!

Click the Regions tab, then follow the link to the Ecoregions Locator page. Put in your home address and click on the map when the search is complete. Your ecoregion will pop up and when you click on it, it will give you a list of the plants in your specific ecoregion or the next level up. **BE SURE to click the NATIVE PLANTS list. In my case, Piedmont Uplands was too specific but they have a list for the next level up, Northern Piedmont). This provides a list of 1596 native plants. Click on any plant to find out many more details about it. You could either bookmark this list in your internet browser or print/download each page to create a list of the native plants in your broader ecoregion.

Advanced Options: Exploring natural vegetation classifications and plant communities

There are a number of different plant classification and organization systems available to the public. Some have been developed for wildfire management; others for natural resource classification and management; and still more for species conservation and understanding biodiversity. Buckle up and see what you can find out about your area!

First, to find your natural vegetation group, go to the National Vegetation Classification ArcGIS map viewer.

To make it easier to narrow in on your spot, hide the coloration by clicking on the little eye that appears when you hover your mouse next to the layer name on the left.

Zoom in to where you live.

Turn the vegetation classification layer back on by clicking the little eye again.

Click the closest colored tile to where you live. An info box will pop up with details on the vegetation type found there.

Copy the GNAME - group name. For me it was “Quercus alba - Quercus montana - Carya glabra Forest & Woodland Group”

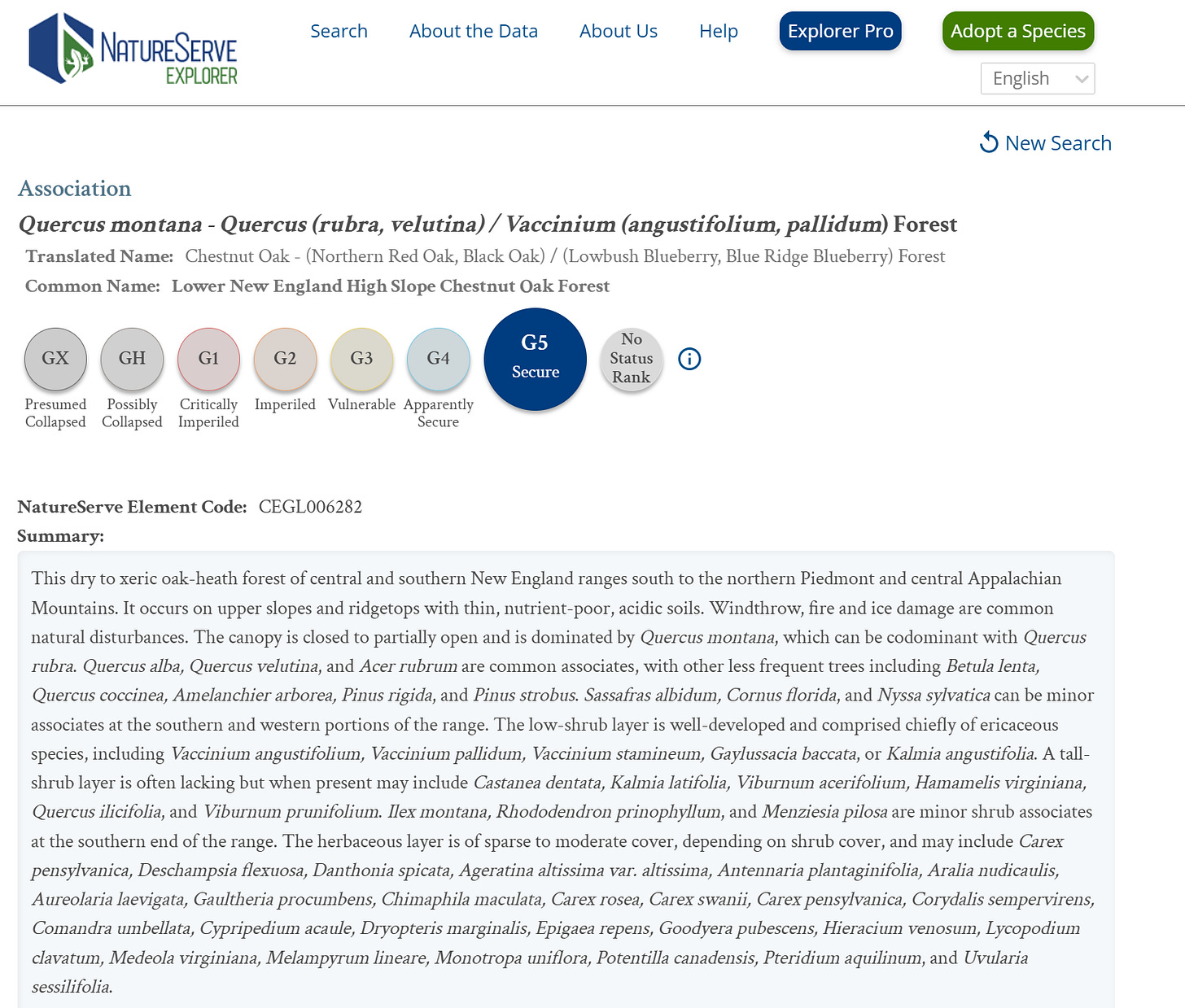

Next, go to NatureServe Explorer and click the search option at the top.

Paste in your Group name and click on the ecosystem that comes up (hopefully you get a match)

This brings up a page with a description of this vegetation group, including a discussion of the dominant species, underlying physiographic influences, and other management and conservation information.

Scroll down until you get to “Lower Level Classifications.” Pick one that sounds likely and click the link to open another page with information on that plant community. Note the CEGL codes in the page, which stand for Community Element Global classification. One of the CEGL codes I found that sounded possible for my area was called “CEGL006282 Quercus montana - Quercus (rubra, velutina) / Vaccinium (angustifolium, pallidum) Forest Association”.

OK, so what did that net us? The end result at this stage is the discovery of your underlying landscape type that helps you to learn what to expect, what to look for, and a better idea of what kinds of plants will do well where you are planting.

For even more detail, you can look for information from your state’s department of conservation (or similar name). Here in Virginia, I took the following steps:

Go to the Virginia DCR site and click on Natural Heritage in the top menu and then choose the Rare Species and Natural Communities page.

Go to Table of Contents, Terrestrial Systems, then look through to see if you can figure out which group is closest to the ones you have discovered so far. Read about them and then you can download summary compositional statistics about each community with plant species. The one I explored was Acidic Oak-Hickory forests. Scroll to the bottom for the downloadable Excel spreadsheet link and look for similar CEGL code numbers to the ones you found on the NatureServe website.

End result: lists of plants that occur together in nearby natural communities with some idea of their commonness and dominance. This takes a lot of noodling around and exploring. There may be more direct ways of finding this information, so if you have any tips and tricks, please share!

Congratulations, you made it!

If you have stuck with me this far, then we should be besties. Seriously! This is pretty niche stuff, but it’s actually not that difficult if you have some breadcrumbs to lead the way. I highly recommend bookmarking these sites so you can go back and check them out over and over. The point is to begin to get a feel for what plants grow together naturally. That knowledge will start to give you an intuition for what will and won’t work in your garden when you see a plant for sale and think, “ooh! I wonder if I should try that!”

Even though it might seem like this is a bit of a rigamarole, by exploring your local ecoregion, your natural vegetation classification types, and native plant communities, you are enriching your store of knowledge little by little. Soon you will feel quite a bit more confident as you work toward designing a successful ecological landscape. And if you would like any personalized assistance, please send me a message and I’d be happy to help you navigate the process!

Next week we’ll start talking about how to actually find plants that will work well for you. Thanks for following along. 🌳

Just WOW! Thanks for all this information!