A Bat Week Call for Bat-Friendly Gardens

Let's nurture our nocturnal neighbors

As with many bat-related things, the fact that we have just celebrated Bat Week (October 24-31) may have flown under your radar. Bats and their activities often go unnoticed by us busy diurnal humans.

After all, out of 1,400+ species of bats worldwide, only about ten are active during the day.1 The rest are nocturnal, doing their bat-ly things under cover of darkness. By the way, that high number of species means that while we might think of them as a bit uncommon, in reality, bats are the mammals with the most number of species after rodents. Who knew?!

Despite being diverse and fairly numerous, many bat species are in trouble around the world. As with other animals, habitat loss and quickly spreading diseases pose the greatest risks. North American bats in particular have been suffering due to white nose syndrome, a fungal pathogen that disrupts the bats’ hibernation, causing them to wake up and expend energy when they shouldn’t and leading to starvation.

Benevolent bats

Bats are good business. Ecological business, that is! They are major insect predators, snapping up hundreds to thousands of moths, flies, gnats, mosquitoes, and their ilk every night. In some areas (especially desert and tropical settings), they rank high as key plant pollinators. They also play an important role in seed dispersal, so they are definitely beneficial to have around.

Despite such welcome services, bats suffer from bad PR. Their quick and erratic flight can be startling when they come close. A bat trapped inside your house could also be unnerving (but no more than a cicada, honestly!). Some people fear bats due to their ability to carry rabies, but in reality this is an infinitesimal risk. You’re far more likely to get in a car accident or even be hit by lightning than to catch rabies from a bat, so this is one fear you can let go of. Hooray!

Like all animals, bats ultimately depend on plants for survival, because they either consume plant material directly or feed on plant-eating prey. Many bats also roost and hibernate in trees. It starts with a leaf, folks. You heard it here first. This means that we can garden for bats!

Meet your bats

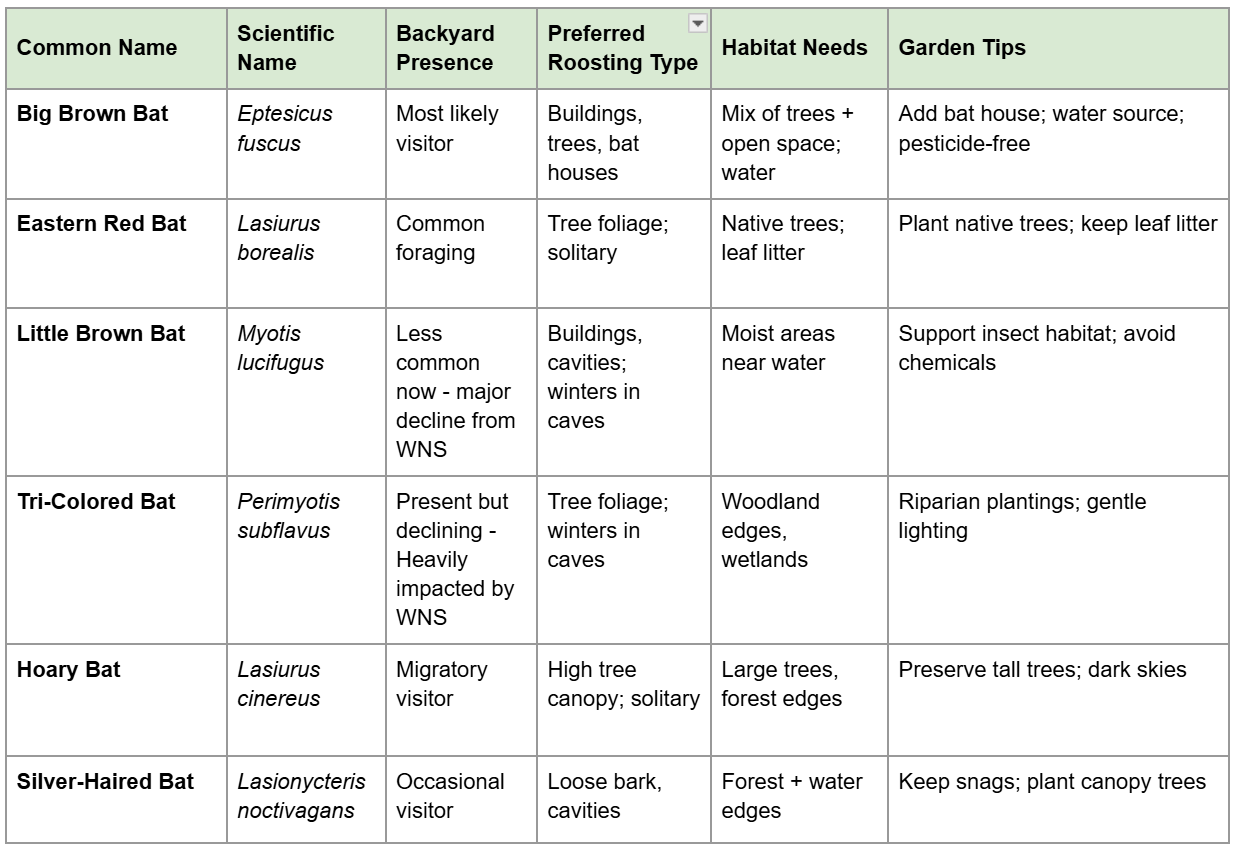

This table lists some of the bat species we would be most likely to observe in the eastern United States, particularly in a garden situation:

As you can see, these days when you catch a glimpse of a bat at dusk or dawn, it’s probably going to be either a Big brown bat or an Eastern red bat. If you see one sleeping during the daytime, look at its size and fur color, as well as where it has chosen to roost. The Backyard Naturalist website has a nice photo identification guide with species information on bats native to Maryland.

What bats do

Bats provide a lot of similar ecological services to birds and bees. Their biggest impact is to control insect populations. All of our bats in the eastern United States prey mainly on insects, and their diet is diverse. Eastern bat species consume ants, beetles, flies, moths, leafhoppers, planthoppers, mosquitoes, and even stink bugs. They are our primary nocturnal insect predators. In southwestern states, there are species that eat fruit or drink nectar (did you know that bats are the primary pollinators of the Mexican agave plants that produce tequila?).

Bats contribute to healthy ecosystems not only by eating insects, but also by depositing high-nutrient feces wherever they fly and roost. Bat guano is very high in organic matter and rich in nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. Where bats congregate in caves, rich guano deposits are plentiful and have long been harvested (quite detrimentally to the bats—and workers—in many cases) for commercial fertilizer.

The presence of bats, conversely, also indicates the existence of a healthy and biodiverse ecosystem. So, if you create conditions that support bats, and you see bats, you know that there abundant native plants feeding insects feeding bats (and birds, and other animals). It is a winning cycle!

A word on mosquitoes

Bats do consume mosquitoes, although mosquitoes are not necessarily their main source of sustenance. They need larger and more nutritious insects to sustain their diet. Other animals on the mosquito-eating team include birds (nightjars, swallows, bluebirds, purple martins, and others including hummingbirds!), freshwater turtles, amphibians, and dragonflies.2

Mosquitoes have their place in the world, and although we do not like them, we need to protect the insect food web. This means selectively suppressing mosquitoes in our yards without using broad spectrum insecticides. All of those companies that knock on your door and mail you advertisements promising to spray for mosquitoes are peddling death to all insects. Avoid them and tell all of your neighbors to do the same. This is really, really important.

Instead, if you have a particular concern about mosquitoes (and yes, there can be risk of diseases like West Nile Virus, Zika, and others carried by mosquitoes), do the following:

Limit standing water around your house such as in gutters, buckets, old tires, etc. If you have a birdbath, be sure to refresh it every few days and this will render it mosquito-free.

Use mosquito dunks in your ponds, bird baths, and water features. Mosquito dunks are little discs that contain the non-toxic (to humans) biological control Bti, or Bacillus thuringiensis israelensis. They are safe to use around bats, birds, fish, pets, and children. In fact, you can try the “bucket of doom” approach, which involves placing a bucket (or you could use something prettier like a pot or dish) with water, some organic matter, a mosquito dunk, and a “rescue stick” to help larger creatures escape, in a shady area away from your home. Female mosquitoes will be attracted to the gross smelly water, and lay eggs there. However, due to the mosquito dunk’s Bti, the larvae that hatch will never reach maturity.

Encourage natural mosquito predators by planting native plants that draw birds, bats, and amphibians. Create a water feature that attracts frogs, toads, and dragonflies. This promotes a natural balance that allows for ecosystem control rather than requiring chemical control. Did you ever stop to wonder why there are whole government entities dedicated to mosquito spraying? Perhaps it is due to the fact that so much of the developed areas do not support these natural predators.

Avoid chemical sprays and mosquito fogging. “Mosquito spraying” is actually insect spray - it does not simply target mosquitoes, but rather kills all insects including beneficial ones. This is the absolute opposite of what we should be doing, because it disrupts the food web, deprives wildlife of food, and deprives plants of their pollinators. Not good.

The four things bats need that you can provide in your garden

Bats’ basic needs are neither complicated nor particularly unique. In other words, if you are able to provide some of all of these needs, you will not only be supporting bats, but also building a biodiverse habitat that is good for all wildlife in your vicinity. Like us, they need four main things: food, water, shelter, and a good night’s sleep.

1. Food. The fundamental food chain is plants —> insects —> bats. Without insects, there will be no bats. Without native plants, there will be very few insects. Ergo, plant more native plants! Specifically, try focusing on plants that support moth and beetle life cycles, since we know those are two mainstays of bat diets. It is important to create layered plantings, with trees, shrubs, herbaceous, vines, and groundcover plants filling vertical space as well as covering horizontal space. Layers offer chances for more diverse species, movement, and interaction. They also provide cover as animals move around. Here are some suggestions to start:

Trees and shrubs are larval hosts and caterpillar powerhouses.

Oaks (Quercus spp.): Host hundreds of insect species—ESSENTIAL

Black cherry (Prunus serotina)

Willows (Salix spp.) and poplars (Populus spp.)

Viburnums (Viburnum spp.)

Blueberries (Vaccinium spp.)

Spicebush (Lindera benzoin)

Elderberry (Sambucus canadensis)

Herbaceous Plants provide nectar for adult moths and night-active insects. We particularly want to focus on night-blooming plants because they’ll draw the insects that flutter and buzz around nocturnally precisely when bats need them.

Evening primrose (Oenothera biennis): Opens at dusk, pale and fragrant

Goldenrods (Solidago spp.) and Asters (Symphyotrichum spp.): Excellent late-season support

Native milkweeds (Asclepias spp.)

Joe-Pye-weed (Eutrochium spp.)

Bee balm (Monarda didyma)

Native sunflowers (Helianthus spp.)

2. Water. Remember, you can provide all of the water features you want without worrying about mosquitoes via the magic science of mosquito dunks, so do not be afraid to create a wildlife pond! Bats drink while flying, so they need room to swoop down and skim along the water’s surface. Ideally, they like a clean, open water source that is 7-10 feet long. This gives them enough room to safely maneuver. This might look like a trough, a stock tank, a small pond, or an open stream if you are lucky enough to have one.

3. Shelter and roosting sites. If you glanced at the table above summarizing a few of the most common bats found in the eastern US, you might have noticed that most of them like to roost in trees. Bats don’t have a lot of natural weapons for self defense. They rely on hiding and being still during the day to escape predation. Thus, they like small places where they can tuck themselves away and go unnoticed. Bats use dead trees and their cavities, spaces underneath bark, deciduous foliage, and even leaf litter piled up on the ground. So, to offer natural roosting sites, provide the following whenever possible:

Dead trees (snags), especially oaks and poplars. Leave snags standing when possible. If you have to remove a tree on your property, ask your arborist if they can do a “snag cut,” which means they cut it at a height of 10-20 feet (or taller) and leave it for wildlife use.

Plant trees with shaggy, loose bark. The aptly named shagbark hickory (Carya ovata) is known to be a popular species among bats. These are gorgeous trees with strong wood and luminous golden fall color. Additionally, the nuts are edible for humans and loved by many animals. Give one a try!

Keep leaf litter and woody debris wherever possible in an undisturbed state. You wouldn’t want to mow, blow, or rake up a sleepy bat!

As a supplement, you can also consider installing a bat house, but be aware that bats will almost always choose a natural roosting site over a human made one. It could take months or years for bats to inhabit a bat house, and they might never use it (sorry, just being honest). If you put one up, you’ll have better luck attracting a resident bat if you can install it 15-20 feet high on a south-facing pole or tree where it gets full sun and has an open flyway below. Being near water gets you bonus points.

4. Dark skies. Finally, bats are creatures of darkness. They don’t need a lot of light to find their prey, and artificial light can disrupt their foraging and navigation. If you need to put up exterior lights, try to turn them off when you go to bed, or use motion-sensor switches so they are off most of the time. Shield the lights so they only shine downward; never up toward the sky. Try to choose light bulbs on the warmer (aka yellower) end of the visual spectrum, such as those below 2700K. But the watchword is DARK, so turn off or minimize outdoor lighting as much as possible. This not only benefits bats, it also helps migrating birds, owls, nightjars, moths, and wildlife in general.

To summarize: garden design for bats

Designing your garden to attract and support bats looks a lot like gardening for birds, moths, bees, and amphibians. I love this overlap. Remember these keys and you will be well on your way to attracting our friendly flying mammal friends:

Choose native plants: Go for keystone plants that support a wide variety of insects, especially moths and beetles. For extra credit, plant night-blooming species.

Layered plantings: Create canopy, understory, and groundcover diversity.

Avoid pesticides: Definitely do not spray for mosquitoes. Say no to any synthetic chemicals that are dangerous to a broad range of insects. To control mosquitoes, use mosquito dunks and try a “bucket of doom.”

Reduce lawn: More natives, less turf is always a good mantra.

Embrace a natural look: Leave snags, woody debris, leaf litter wherever safe and possible.

Water features are vital: If you have room for something longish (7-10 feet), try it out! Wouldn’t it be so cool to watch a bat swoop down and take a sip one evening?

Sooo, are they here?

How do you know if you have bats? Well, you probably need to go outside at dusk or dawn. Sounds obvious, but unless you have a dog that needs walking, you might not regularly do this! Try sitting outside for 20 minutes or so after sunset. Look up toward the sky and keep an eye out for fluttery, erratic fliers. If you have really good hearing, you might also just be able to hear some very high-pitched chirps, squeaks, or clicks, which are the vocalizations bats use to echolocate. Their echolocation abilities help with navigation, hunting, and communication with other bats. There are actually bat detecting devices (ultrasonic microphones) and phone apps that when activated allow us to hear echolocation sounds: check out the Echo Meter Touch 2, for example.

Many bats, like birds, migrate in spring and fall, so those can be good times to look for bats. In the eastern US, most bats either migrate or hibernate, or do a combination of both. Here in the mid-Atlantic, I have definitely seen bats even in winter, suggesting that this could represent the southern portion of some of their ranges. Overall, you might be more likely to spot bats during spring, summer, and fall.

Bring on the bats

If you are an ecological gardener, you’re probably already gardening for bats in some way. Gardening for bats is holistic: plant native plants, don’t use pesticides, keep things dark at night, create a clean and open water source. Every step strengthens the food web which provides bats what they need. By doing one or all of these things, you’re supporting biodiversity from soil to sky, which is a very worthy and worthwhile thing to do!

Please share in the comments with all of us: Have you seen bats in your garden, yard, or neighborhood?

Most bats don’t echolocate in broad daylight. Here’s an exception. Sharon Oosthoek, Science News, April 15, 2022.

Meet the Squad of Mosquito-Eating Species. Jane Kirchner, NWF Blog, August 16, 2022.

I remember the first time I heard about "bat houses" and went out and got one for our cabin on Toothaker Island. Thanks for all this great information!