Ecological Gardening to Beat the Heat and Drought

The top 4 things you can do to make your garden more resilient

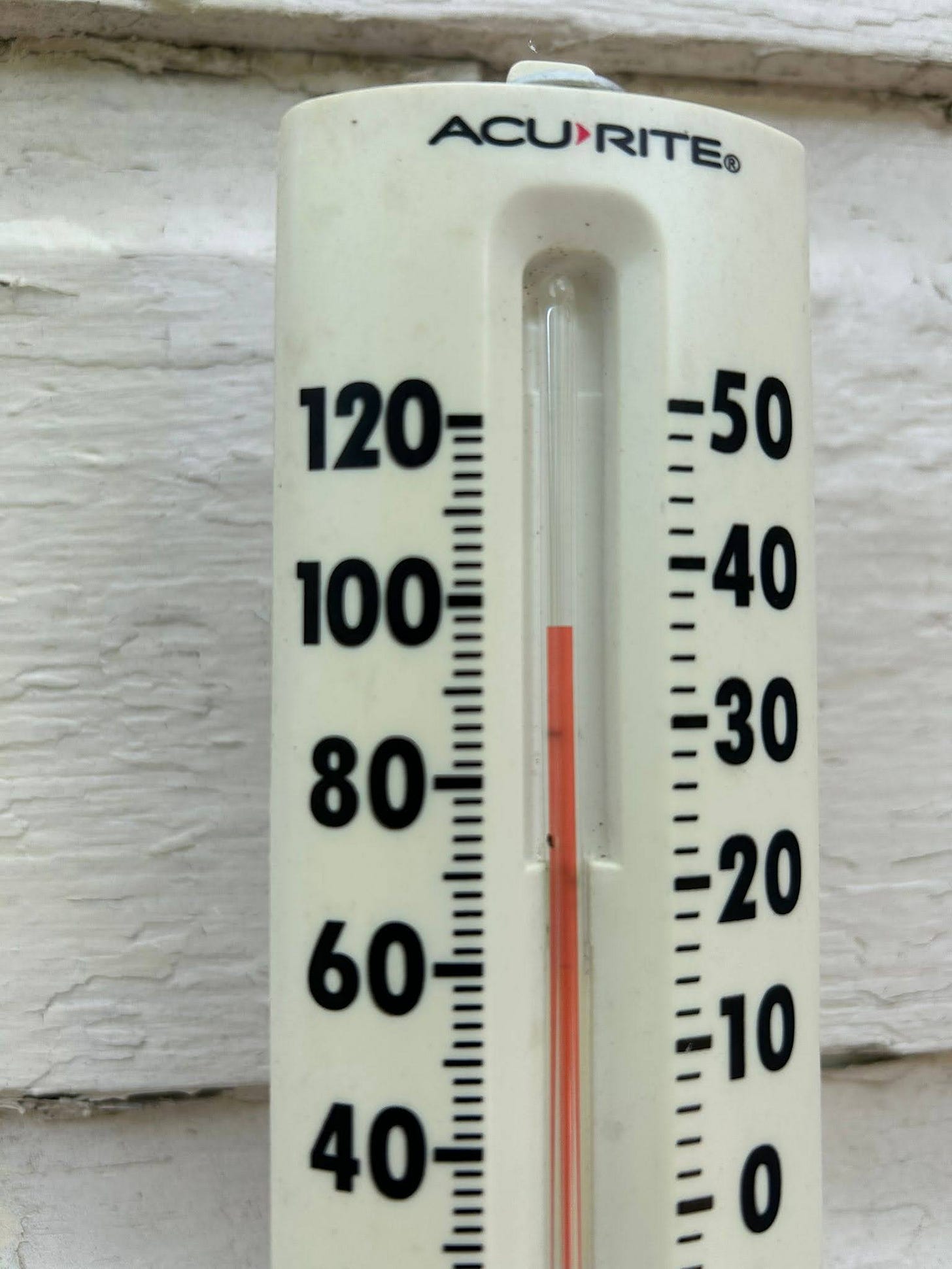

As the cooler, wetter (or not!) conditions of spring transition into the heat of summer, gardens can begin to look stressed fast. This is especially true during weeks like this past one, when a sustained heat wave covered so much of the US. Climate modeling predictions point toward longer, more severe, and more frequent heat waves and droughts in the future.1 Naturally, gardeners will be searching for strategies to meet those challenges.

When it is sunny and 90+ degrees for even a few days in a row, soils dry out and many plants suffer. Growth and biological function slow down, photosynthesis is impaired, and when it is too dry, the plants wilt. If conditions stay dry for too long, plant tissues die.

What to do?

First of all, experience is showing us the truth of the predictions. There is no denying that we keep having the warmest year on record nearly every year, and many of us have experienced several extended droughts recently. So we need to recognize this shift in conditions, expect more of the same (or worse) in the future, and try to either adapt or mitigate the effects.

Here are the top four things that ecological gardeners can do to make your garden more heat and drought resistant:

#1 - Add Organic Matter

Whether your soil is solid clay or super sandy or rocky, or any combination thereof, your top priority should be to add organic matter in the form of compost (ideally). You can also use shredded leaves, straw, wood chips, aged manure, dry grass and weed clippings, seaweed, or whatever you can get your hands on. The more composted the material already is, the fewer complications you’ll have.

Compost is partially decayed organic matter. It is still biologically active and full of beneficial microbes. It’s full of nutrients that are available for plants to use. In the context of this article, though, compost’s superpower lies in its ability to improve soil condition. As the microbes and small pieces of undecomposed organic matter settle into the soil, other detritovores (creatures that eat and digest and process organic material) bring pieces down deeper into the soil horizon. This movement of both material and small animals creates holes, or pores, in the soil. Soil needs those pores so that water can infiltrate and percolate down to the groundwater. Roots need pores to get access to both air and water. In fact, did you know that healthy soil is about 50% air?

Increasing soil organic matter through the addition of compost helps your soils support healthier, more resilient plants that can withstand periods of heat and drought. With improved structure, soil can retain what moisture it has for longer periods of time (picture a sponge holding water versus water draining straight through a bucket of sand or sheeting right off a parched cake of clay). This sponge-like quality gives your plants a little boost so they can keep growing and functioning longer even when conditions are hot and dry.

The general recommendation is to add about one to two inches of compost each year to your planted areas. You can sprinkle it on top of the soil and leave it like that or gently rake it in. This is known as top dressing, and it simulates the pattern of leaves, twigs, branches, and dead vegetation falling onto the ground and gradually decaying into the soil. Let the soil-dwelling creatures do the work of mixing in the compost deep into the soil.

One note about this: as ecological gardeners, we are at times exhorted to add organic matter, and at other times we are told not to amend the soil, and to simply choose plants best adapted to our site. This is a nuanced topic. If your site happens to be in an urban or suburban area, and your soil has been significantly disturbed at any point since construction, then you are probably not dealing with natural soil. In this case, amending the soil may well be the best strategy, because the soil structure has been compromised. Improving soil structure and nutrient levels will help your site to support a greater number of happy plants and animals.

If you are dealing with natural soil that is similar or identical to the soil in the forests, valleys, and hills all around you, then consider whether you need to add as much, or any, compost. If you are chopping and dropping when you trim weeds and dead plant material; or if you are leaving your leaves and allowing them to decompose on site rather than raking or blowing them away, then the soil nutrient cycle may remain intact. In this case, place more attention on your plant choices. Unfortunately, this is not the situation for most gardeners today in the United States. Most of us live with disturbed soil. Thus the encouragement to add organic matter.

#2 - Capture rainwater on your property

When it does rain, the more water you can hold on to is usually better. Again, in an ideal situation, the rainwater would infiltrate into the soil through pores (air pockets) and slowly trickle downwards in the soil column until it reached the groundwater table. This is how aquifers get replenished. This slow soaking in and sinking downward also provides the optimal amount of water in the root zone where your plants are growing. It also means that your soil will hold on to the organic matter that’s on the surface, rather than it washing away during a storm.

In urban and developed areas, where there is a lot of impermeable surface such as pavement, concrete, roofs of buildings, and the like, the soil is covered up and cannot accept rainwater. Or the soil has become compacted and the pores have been crushed, so water runs off instead of being allowed to soak in. In those situations, rain may soak the top quarter inch or so of the ground, but it has no chance to truly moisten the soil, and things quickly dry out again once the rain stops. Additionally, large and sudden flows of water that run off into storm drains and streams move faster, erode more topsoil, and carry more pollutants downstream into our waterways. The more we can counteract this process, the better.

There are numerous ways to capture rainwater, from setting up rain barrels to preparing and planting rain gardens. You can also replace lawn (which does not capture rainwater well at all) with trees, shrubs, and herbaceous plants. If you have a sloped area and any sort of ditch or gully, you can create check dams that slow and pool the water on its way downhill, allowing some of it to sink in before it continues. Vegetative bioswales are very gently sloped depressions whose intent is to hold on to rainwater for as long as possible before it exits at the bottom of the slope, giving it time to soak down into the soil, catch and hold sediment, and prevent excessive runoff. There is a lot more to be said on this topic, but any efforts you make to keep rainwater on your site rather than letting it run off will improve your property’s resiliency!

#3 - Plant trees

Trees really are the answer to a lot of problems. Picture a forest. When rain falls, it trickles down the leaves and trunks of the trees or hits the leafy forest floor, gradually soaking into the soil. Very little water runs off away from a forest, and what does run off does not do so quickly. The shade from the trees keeps the soil surface cool, buffering temperatures and maintaining moisture for longer between periods of rainfall.

Trees can help your property in the same way. Once established, many species are quite drought resistant because they have larger and deeper root systems capable of drawing more water from the soil. Because trees live for many years, they have evolved to ride out stressful conditions. However, recent data is showing that the increased frequency and severity of heat waves and droughts does negatively affect trees and forests, too. 2 Despite this, it is still worthwhile to plant and care for trees on your property because they provide shade, capture carbon, produce oxygen, make shade, keep temperatures cooler, trap and hold on to rainwater, provide ecological services to many forms of wildlife, and are beautiful to boot!

#4 - Choose resilient plants, and plant thickly

Knowing what we now know, that heat waves and droughts are no longer a rarity, it’s important to choose your plant palette accordingly. Heat and drought tolerant or drought resistant plants3, once established, will need less care and watering during stressful periods. This does not mean you can plant and forget them. All plants need careful tending and regular watering for at least one to two growing seasons to get established (and trees may need up to five years of supplemental watering). Even during droughts, you may need to do some watering if you want to prevent plant die-off among certain species. Plant performance is species-, specimen-, and site-specific, so you’ll need to use your powers of observation to determine the best care regime.

In general, plants that can remain resilient in hot and dry conditions often have one or more of the following characteristics:

small leaves

waxy leaf coating

hairy leaves or stems

silver colored leaves

fleshy, succulent tissues that store water

deep roots

(sometimes) milky sap

Happily, many of those characteristics also make the plants deer resistant as well, as I discussed in last week’s post.

Trees, shrubs, and grasses tend to be your friend when it comes to heat and drought resilience. When researching species, look for sources that mention xeriscaping, which means landscaping to reduce or eliminate the need for irrigation. Now, many of us live in places that have both wet and dry periods. A plant that is evolved to live in a desert might not work when it has to live through months of cool, wet weather, so you will need to read descriptions carefully, know your site, and use trial and error.

Planting thickly ensures that the soil surface remains shaded nearly all the time. Whether shaded by trees, shrubs, or herbaceous plants, it’s far better for a site to be mostly or completely covered by plants. The “plant - sea of mulch - plant - sea of mulch” method of landscape design leaves a lot of open ground exposed to sun and wind, which dry it out. Mulch does help to hold moisture in the soil; however, it can also keep water from infiltrating down to soil level unless it is a good soaking rain. It can also prevent plants from spreading or reseeding if it is too thick.

Here are a some of my top suggestions for plants to beat the heat and drought. Google the species and BONAP to check for nativity in your area:

Trees

Hickory species, including bitternut, pignut, and mockernut (Carya cordiformis, C. glabra, C. tomentosa)

Hackberry, Celtis occidentalis

Green and cockspur hawthorn (Crataegus viridis and C. crus-galli)

Common persimmon, Diospyros virginiana - this extremely adaptable grows in all conditions from sand dunes to swamps!

American holly, Ilex opaca

Eastern red cedar, Juniperus virginiana

Pine species, including Eastern white, Virginia, loblolly, and shortleaf pine (Pinus strobus, P. virginiana, P. taeda, P. echinata)

Certain oak species including chestnut, scarlet, willow, and blackjack oak (Quercus prinus, Q. coccinea, Q. phellos, Q. marilandica)

Sumac species, including smooth, winged, and staghorn (Rhus glabra, R. copallinum, and R. typhina)

Shrubs

American beautyberry (Callicarpa americana)

New Jersey tea (Ceonothus americanus)

Northern bush honeysuckle (Diervilla lonicera)

Oak leaf hydrangea (Hydrangea quercifolia)

Shrubby St. John’s-wort (Hypericum prolificum)

Inkberry holly (Ilex glabra)

Bayberry or wax myrtle (Morella pensylvanica or M. cerifera)

Fragrant sumac (Rhus aromatica)

Maple-leaf or blackhaw viburnum (Viburnum acerifolium or V. prunifolium)

Grasses and Sedges

Certain sedge species, including Appalachian, white-tinged, and plantain-leaved (Carex appalachica, C. albicans, and C. plantaginea)

Sideoats grama (Bouteloua curtipendula)

Woodland sea oats (Chasmanthium latifolium)

Poverty oatgrass (Danthonia spicata)

Bottlebrush grass (Elymus hystrix)

Purple lovegrass (Eragrostis spectabilis)

Hair-awn muhly grass (Muhlenbergia capillaris) - doesn’t do well with winter wetness

Little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium)

Ferns

Common or southern lady fern (Athyrium filix-femina or A. asplenoides)

Marginal wood fern (Dryopteris marginalis)

Hay-scented fern (Dennstaedtia punctilobula)

Christmas fern (Polystichum acrostichoides)

Vines

Trumpet-creeper (Campsis radicans) - can be very aggressive

Coral honeysuckle (Lonicera sempervirens)

Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus virginiana) - can be quite aggressive, and can cause skin irritation in certain people

Coralberry (Symphoricarpos orbiculatus)

Herbaceous plants

Super-duper drought resistant:

Prickly-pear cactus (Opuntia humifusa)

Adam’s needle (Yucca filamentosa)

Woodland stonecrop (Sedum ternatum)

Rattlesnake master (Eryngium yuccifolium)

Yarrow (Achillea millefolia)

Sweetfern (Comptonia peregrina)

Common dittany (Cunila origanoides)

Butterflyweed and common milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa and A. syriaca)

Blue or yellow wild indigo (Baptisia australis or B. tinctoria)

Creeping phlox (Phlox subulata)

Spotted horsemint (Monarda punctata)

Dwarf crested iris (Iris cristata)

Blue-stemmed or rough-leaved goldenrod (Solidago caesia or S. rugosa)

Aromatic or blue aster (Symphyotrichum oblongifolium or S. laeve)

Ohio or Virginia spiderwort (Tradescantia ohiensis or T. virginiana)

Eastern bluestar (Amsonia tabarnaemontana)

Scaly blazingstar (Liatris scariosa)

Green-and-gold (Chrysogonum virginianum)

Golden ragwort (Packera aurea)

Wild geranium (Geranium maculatum)

Alumroot (Heuchera americana)

White wood aster (Eurybia divaricata)

Eastern red columbine (Aquilegia canadensis)

Black-eyed Susan or orange coneflower (Rudbeckia hirta or R. fulgida)

Whorled or tall coreopsis (Coreopsis verticillata or C. tripteris)

Download a .pdf version of this list below:

Let me know how you are faring in the heat! And what has worked for you to make your ecological garden more resilient in the face of heat and drought. Really, please leave a comment or ask questions so I know at least a few humans are reading my posts - it means a lot!

For example: Global climate predictions show temperatures expected to remain at or near record levels in coming 5 years - World Meteorological Organization, May 28, 2025.

For example: Hammond, W.M., Williams, A.P., Abatzoglou, J.T. et al. Global field observations of tree die-off reveal hotter-drought fingerprint for Earth’s forests. Nat Commun 13, 1761 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-29289-2

Drought tolerant plants are those that are able to withstand certain dry or droughty periods, although they may suffer and not look their best. Drought resistant plants can handle drought conditions with aplomb and even flourish, because they have evolved special adaptations.

In my early experience (after killing all the grass and starting to fill in with natives), it seems clear that wood chip mulch significantly helps with moisture retention and therefore new plant growth is increased. Piedmont region, NW VA.