Several recent personal events have me reflecting on the juxtaposition of life’s fragility, beauty, and continuity. A dear friend of mine died a couple of weeks ago, a very final event, wrenching and inarguable. This and other tumultuous happenings remind me how very little control we have in our lives, how short and unpredictable our time is. And yet life continues ever new and full of beauty if one can but relax enough to appreciate it. As National Moth Week comes to a close, I’m reminded of how moths symbolize ephemerality, tenderness, and at the same time deep persistence. Their individual lives are very brief, yet with their delicate and subtle beauty and diversity, they contribute profoundly to our world.

The quiet beauty and significance of moths

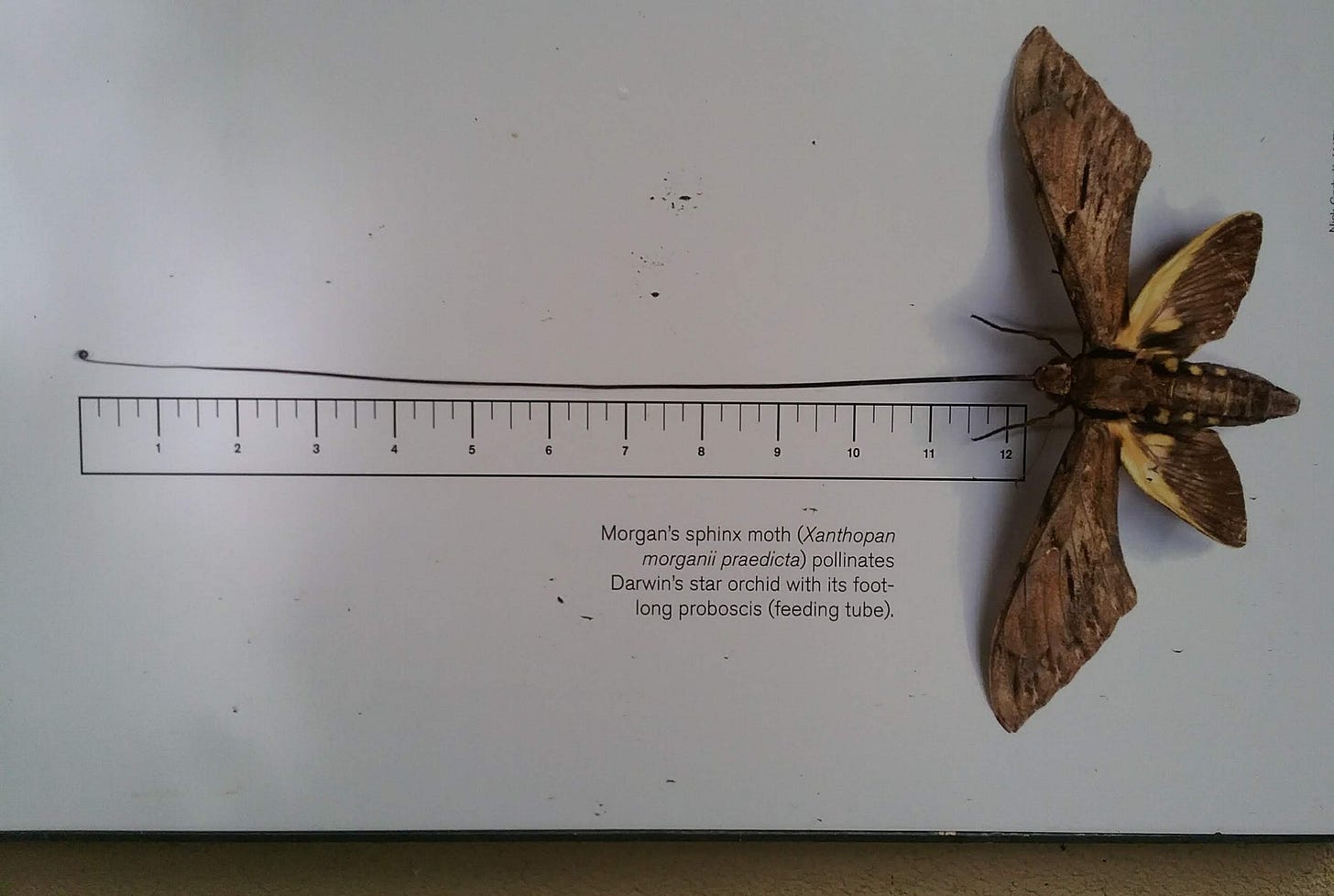

Most moths go about their entire lives unremarked by humans. Worldwide, we have an estimated 160,000 species of moths(!). That’s almost ten times more than butterflies, of which there are about 17,500 species, though the butterflies often get more attention. Moths evolved about 300 million years ago, before dinosaurs appeared. Early ancestors of today’s moths probably consumed bryophytes, which are non-vascular, non-flowering plants. Later, when angiosperms (flowering plants) started to evolve and diversify, moths developed proboscises, the extendable straws that lets them suck up nectar, sap, and other liquids. Butterflies appeared around 100 million years ago.1

Many (though not all) adult moths are nocturnal, seeking food and mates under cover of darkness while humans sleep. As well, moths tend to rely more on camouflage coloration for protection from predators, while butterflies have evolved bright colors as warnings of their inherited toxicity from the plants they consume while in caterpillar form. Butterflies are also mostly diurnal (active during the day), and rely on their bright colorings to attract mates and communicate.

Fun fact about moths: moths and their bat predators have been co-evolving for millions of years. Many moths possess ears that allow them to detect bat echolocation and take evasive action. However, scientists recently discovered that, contrary to earlier theories, the emergence of bats did not precipitate the evolution of ears in moths. In fact, moths developed ears way before bats came to be. However, once bats DID evolve, moths began to develop additional evasive features to avoid predation. Some moth species that don’t even have ears developed “stealth” capabilities, like the luna moth, whose fluttery tails baffle bat echolocation.2

Although we often overlook moths, they are minutely beautiful creatures essential to healthy ecosystems. Moths are important pollinators for flowering plants, especially those that bloom at night. From caterpillar to adult, moths make valuable food sources for birds and other animals. Interestingly, moth caterpillars don’t limit themselves to eating just the leaves and flowers of their host plants. They can also feed on stems, roots, and seeds. Certain moth species even consume fungi, lichen, and decaying woody material.

The precarity of life: Ecosystem change and perspective

Biodiversity is waning right now. We’ve seen a staggering loss of species and overall wildlife abundance over the last 50 years, including insects. I know I am not alone in feeling overwhelmed and sometimes paralyzed by the magnitude of the situation.

Sometimes I contemplate Earth’s geologic time, though (such as the 300 million years of moth life!) and the dynamic, ever-changing nature of ecosystems. We know that there have been five major extinctions, with a sixth underway. During some of those extinction events, over 75% of all species died out! Wait, why am I talking about this doom and gloom? Because: despite the loss of life and sharp contractions of speciation, life on Earth recuperated.

More recently, glacial advance and retreat modified our climate and the distribution of species as well. The most recent glacial period only ended 11,700 years ago, and there were woolly mammoths roaming the land up until about 4,000 years ago - around the time that the Epic of Gilgamesh was written. !! I just learned that mind-boggling factoid from The Weekly Anthropocene’s interview with Dr. Rhys Lemoine, a megafauna rewilding scientist. It is an absolutely fascinating read, not least because it reminds us ecological gardeners that we may be thinking in timescales that are too short. If we base restoration or conservation decisions on a chosen “baseline” ecological condition, that baseline is always somewhat arbitrary. In North America, we often talk about pre-European settlement as a baseline, which is only about 500 years ago. In reality, the coevolutionary timescale that our flora and fauna evolved with probably should at least merit consideration of a time when megafauna were present, so more like tens of thousands of years ago. Evolution is a very long game.

Shown here is a woolly bear, not a woolly mammoth. The caterpillar will turn into a moth, the Isabella tiger moth (Pyrrharctia isabella)! And that is pretty cool too.

But I digress. A bit. Change feels both slow and sudden at different scales, yet Earth’s life persists. It adapts and evolves and continues in multitudinous directions, even if humanity’s place here is not guaranteed. And from a deep time perspective, I find that comforting. As a biophile, someone who loves all life, I—and I presume many of you reading this—feel called to support the continuation of all species. And individual action can be meaningful. Planting a keystone plant species that feeds caterpillars, and leaving leaves through winter, makes a difference to life on Earth.

So…

How to support moths in your garden

The first step is to appreciate and notice them, because they are not always obvious denizens. A few ways to do this include:

Setting up a moth trap. Check out

at Clouded Silver. She has a very cool setup and regularly reports on the moths that she finds on her tiny Scottish island! They all have the best names. Basically, a moth trap is a box or bucket filled with egg cartons, with a funnel and a special light that you set out at night. The moths are attracted to the light and come in, then roost in the little cavities of the egg cartons. They hang out there until the morning when you come along and gently lift them out to observe and release them. A moth trap harms no moths! And the great thing about it is that by the time you are removing the moths, they are all sleepy and quietly sitting still so you can get a good look.Hanging out a white sheet and using a light at night to attract and observe moths. You can use any kind of bright light, or try two or three kinds, like a regular flashlight, an ultraviolet light, and a mercury-vapor light if you have one of those lying around. This can be as low-tech as you want, or you can get pretty fancy with it. Either way, try to find a dark area and make your light the brightest one around. Set it up and wait, and see who comes fluttering in!

Just walking around your garden or yard, peering closely at tree trunks, the undersides of leaves, and flowers. I bet if you look hard enough, you will find at least one moth. And maybe lots. Not all moths are nocturnal, so also keep your eyes out during the day. Sphinx moths and clearwings, the hovering moths, are particularly active at dawn and dusk, and they are super cool to see.

If you are so called, it’s really valuable to report your moth sightings to a citizen science platform such as iNaturalist (that link leads to a special National Moth Week project, but you can submit observations to iNaturalist at any time of year). Data collected in iNaturalist is used by hundreds of scientific research programs and winds up in academic reports.

Plant Nocturnal-Friendly Flowers

Many moths are nocturnal and are especially drawn to white, pink, or purple flowers that open or emit scent at night. Have you heard of a moon garden? It could also be called a moth garden, because it involves planting mainly white, and often fragrant flowers that “glow” in the moonlight.

A few species to try (consult BONAP to confirm nativity in your area):

Phlox, including moss phlox (Phlox subulata, creeping phlox (P. maculata), woodland phlox (P. divaricata), or garden phlox (P. paniculata)

Mountain mint species, especially clustered mountain mint (Pycnanthemum muticum)

Evening primrose (Oenothera biennis)

Buttonbush (Cephalanthus occidentalis)

Coral honeysuckle (Lonicera sempervirens)

Shining hydrangea (Hydrangea radiata), smooth hydrangea (H.arborescens)

Summersweet (Clethra alnifolia)

Grow Larval Host Plants

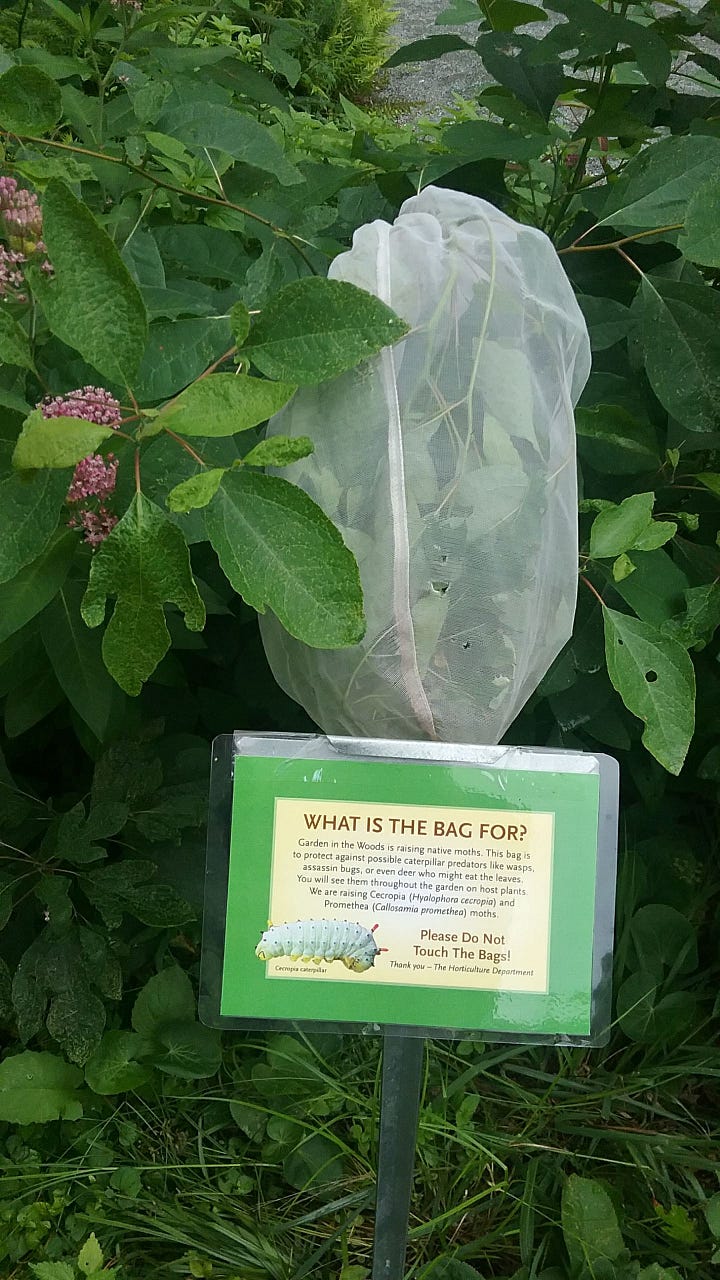

Beyond simply providing nectar for adult moths, it’s crucially important to support moth caterpillars by planting the kinds of plants they eat. If there is a specific species of moth you hope to see in your garden, research its larval host plant and get that in the ground.

Trees will have the largest impact on increasing moth species diversity and abundance on your property. If you have room for keystone species such as oaks, cherries, and willows, they host the greatest diversity of Lepidoptera (moths and butterflies). You can find suitable herbaceous, shrub, and tree species by consulting Homegrown National Park’s Keystone Plants Finder to identify species that occur in your greater ecoregion.

Provide habitat and shelter

The final element you’ll need to to support moths in your garden is to give them the conditions they need to complete their full life cycle. It is not enough to plant night-blooming flowers and larval host plants if you then trim, rake, and blow away all of the leaves for the winter to “clean up” your garden. In doing so, you will have removed many overwintering moths at various stages of growth. Moths survive the winter as eggs, larvae, pupae, or adults, depending on their species. Some hide behind bark crevices, some cling to branches or twigs, but many of them are on or near the ground, sheltering in the leaves and vegetative matter. Allow as much leaf litter, sticks, twigs, and wild spaces in your garden as you can for shelter and overwintering habitat.

If you are in a suburban or urban area and cannot leave all of your leaves for the winter, see if you can rake (not blow, and not mow) at least some of them under and around a tree, or into a garden bed at the back or side of your property. This may help to retain and protect a portion of your moth population.

The more you can keep the area underneath trees covered in mixed vegetative cover, the better. This is the concept of providing “soft landings,” or areas where insects can fall, crawl, or fly down to complete the next stage of their life cycle in safety. To create and maintain soft landings, plant a mix of native plants under your trees out to their drip line (the farthest reach of the branches and leaves away from the trunk). Do not mow and do not heavily mulch this area. Instead, leave it alone as much as possible to minimize disturbance to the insect life there.

Broadening perspectives

As with any form of ecological gardening, gardening for moths is not just about plants and moths, but about fostering a dynamic, resilient ecosystem. In these posts I’ve been publishing that focus on specific aspects of gardening for wildlife, the point is that you can express your particular focus or interest—be it supporting birds, turtles, frogs, or lepidopterans—but whatever you choose, you will be contributing to a more biodiverse world. And that is meaningful.

We can’t individually save the planet or stop climate change or halt mass extinctions because we don’t control enough land and resources on our own. However, our combined personal actions DO make a difference, both to the world at large and to ourselves. Taking action and doing what we can, where we can, objectively and subjectively moves the needle in a positive direction.

When we understand the shifting context of landscape change and the longer arc of earth’s history, we can deepen appreciation for ephemeral beauty. This perspective also relieves some pressure, because it reveals that there is no one right answer to ecological preservation elements. When everything is undergoing change, ebbs and flows can be seen to be part of a much larger web of processes. We can both take action and release the need to be perfectly in control.

This National Moth Week, let’s slow down, look more closely, and make space for the quiet, ephemeral yet ongoing presence of moths in our gardens and lives. In honoring their place in the ecosystem, we honor the interconnectedness and the fleeting beauty of all life.

Butterflies and plants evolved in sync, but moth ‘ears’ predated bats. Natalie van Hoose, October 21, 2019.

A Textbook Evolutionary Story About Moths and Bats Is Wrong. Ed Yong, The Atlantic, October 21, 2019.

A wonderful read. Thank you. I also, sometimes feel overwhelmed by the enormity of the climate, nature, extinction etc issues and your fresh, new (for me at least) perspective is something good, something to think about. Thank you. I am constantly looking at my garden and how I may improve the habitat for as much life as possible. I am only just learning about the specifics of moths (and their caterpillars) needs so this was good to see dropping in to my inbox ❤️

Excellent - thanks. I just discovered your newsletter, looking forward to more.